The Treepex Case: Learning More About Fake News Proliferators By Using Domain Search Lookups

Back in 2017, a startup presented a revolutionary product to the world, one that would allegedly change the way people breathe. Treepex, a portable device that cleans the air as you breathe sparked many conversations, causing it to become viral. Thousands of people viewed the product video. And the startup founders, Bacho Khachidze and Lasha Kvantaliani, even appeared in interviews from big news sites, including the Associated Press (AP) and The Huffington Post.

The irony is that Treepex never existed, at least not as a physical device. In an interview with Inc., Khachidze and Kvantaliani admitted that their goal was to prevent products like Treepex from needing to exist. The Georgian duo shared that their business has to do with planting trees instead. And they exerted effort to make Treepex go viral only to raise awareness about the growing issue of pollution.

They did that. They tricked people and even reputable news sites into thinking that their offer was real. (Note: Both AP and The Huffington Post subsequently removed the interviews from their sites).

Here are the details from The Huffington Post follow-up report:

- Khachidze and Kvantaliani know that illegal logging is a growing problem in Georgia and that air pollution is a global concern. They wanted to address that issue.

- They developed the app Treepex to get people to send money in exchange for the startup planting a tree on their behalf. The app did not gain enough traction, though.

- The Georgian duo then collaborated with a few other people to think of ways to make people wake up to the importance of trees to the environment without spending a dime.

- They decided to “invent” a gadget that supposedly used plant DNA in its filter and would turn carbon dioxide into oxygen because they know people support technological breakthroughs.

- The group hired a designer to create a fake device and launched a promotional video.

- Soon, AP requested an interview. The group used the opportunity to meet their end goal. AP released a short clip, and Treepex became viral. Buyers, sellers, and investors wanted to get hold of the product. The promotion even reached parts of Asia such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and China, where air pollution is a pressing concern.

- In the end, the fake news of the gadget successfully reached 26 million people worldwide, based on the group’s monitoring software.

- The group eventually released a video admitting Treepex’s device was a hoax.

The Treepex case makes one wonder what would happen if the viral content had been developed by malicious individuals whose only goal was to siphon off money from their victims? And what could have happened if reputable sites had given them credibility, thus unknowingly helping them? Most importantly, how then can users stay safe from known fake news proliferators?

Our Investigative Tools: WHOIS Search and Others

Viral videos tend to score millions of viewers. Should their owners turn out to be fraudsters, they can quickly instigate an attack by infecting the viewers’ computers with malware. In light of this, the first thing that users need to do is differentiate what is real from what is fake. For that, they must know the three distinct characteristics of fake news:

- It is not factual.

- It is developed to become viral.

- It is meant to distort beliefs by preying on bias or prejudice.

One way to check if the news is fake is by looking at its publisher, although, as the Treepex case shows, going for reputable news sites may not be enough. Readers should learn to dig deeper, especially if they are thinking of investing in or buying a product.

Even then, it’s not always possible to spot fake news right away. However, one may take measures to stay protected from people known to have spread fake news in the past and avoid being scammed again. How so?

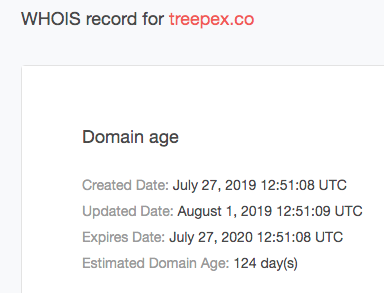

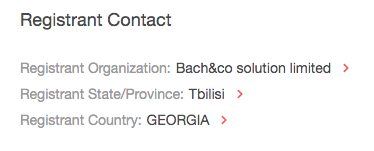

In the featured case, affected users can start by doing a domain lookup on Treepex via WHOIS Search. A search for the domain treepex[.]co shows that it was registered just this year by an anonymous registrant in Tbilisi, Georgia. (Note that this is the country the company’s founders are from.)

When gauging the reputability of a company, its domain is an excellent place to start. In this case, we see that even though Treepex launched a product in 2017, its site was only put up this year.

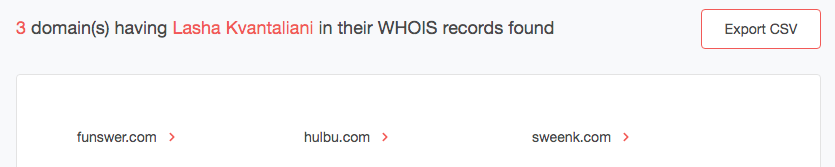

We then ran the founders’ names through Reverse WHOIS Search just in case they had other domains that may be worth looking into. Khachidze had no other domains, but our query for Kvantaliani turned up three results.

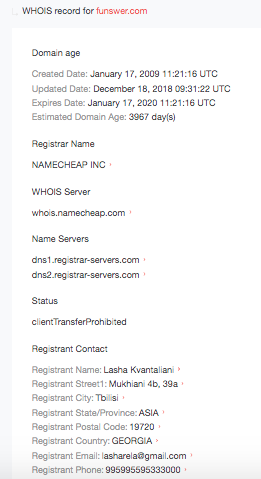

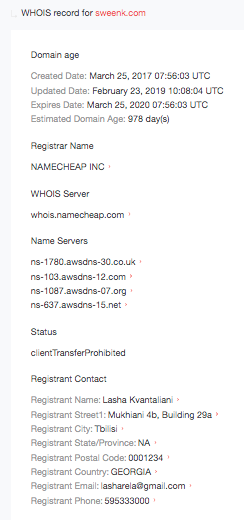

We built WHOIS reports for each domain to find out more about their owners. As it turns out, Kvantaliani may own at least two of the resulting domains, funswer[.]com and sweenk[.]com.

Should history repeat itself, the registrants may use these domains too for deceitful marketing campaigns, so they are probably worth watching out for.

Based on the latest Huffington Post interview, Khachidze and Kvantaliani moved on to another venture — an app that lets users plant a vine in exchange for a bottle of wine. They may or may not resort to the same tactics used for the anti-pollution gadget, but it’s always better to take an ounce of caution.

Users can include the domains treepex[.]co, funswer[.]com, and sweenk[.]com on Domain Monitor, for instance. That would alert them to related domain activities (if ever). Adding Bacho Khachidze and Lasha Kvantaliani to Registrant Monitor may also be a good idea to monitor these registrants’ possible next steps — e.g, new domain registrations, etc.

Overall, this case shows that even reputable news sites can be duped by fake news. The usual recommendation to only rely on reputable sites for information, among other tactics, may not work.

That said, it’s possible to use technical tools to verify claims by learning more about fake news perpetrators and keep them on the radar. But this is not to say that all fake news should succeed in proliferating. Here’s what readers can do.

Best Practices to Avoid Falling for Fake News

Be Critical

Just because something is believable doesn’t mean it automatically is. If the story has great “shock” value, then you can’t be overly critical. Keep emotions in check. Always rationally approach news. Ask why a story was written.

Check the Source

If the source is unheard of, dig deeper. See who the publisher is. Check the site’s URL too. Top-level domains (TLDs) apart from .com, .net, or .org can be suspicious as new gTLDs are known for abuse. Make sure the source is not known to exaggerate.

Corroborate the Story

Look for the story on the sites of other news publishers. However, do not click on links embedded in the story. Go to the publishers’ home pages and search from there. Fake news peddlers can also fake links to supposed sources.

Look for Evidence

Real stories include facts. They should have expert quotes, survey data, and official statistics. Still, make sure those have not been “twisted” to support a claim.

Spot Fake Images

Anyone can edit images and videos to support false claims. Use services such as Google Reverse Image Search to check if those have been altered or used in the wrong context.

Use Common Sense

If a story sounds too good to be true, it most likely isn’t. Fake news is meant to feed on biases or fears.

The Treepex story teaches us that not everything that goes viral and is published on the Web is trustworthy. Our brief analysis also showed that doing domain lookups with tools such as WHOIS Search and others can serve as a starting point for digging deeper into a site and its owners’ reputation. This approach can help users learn more about fake news proliferators.