Privacy or Accountability: What the Redaction of WHOIS Data Means for Cybersecurity

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- WHOIS After the GDPR: Who Can See Who?

- Redaction of Contact Emails: The Data

- Redaction of Contact Emails: The Implications

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

WHOIS data has usually been the starting point for security professionals, incident responders, and forensic investigators when a suspected cyber attack takes place. WHOIS registrant, administrative, and technical details are deemed reliable by investigators, as using fake registrant credentials when purchasing a domain is a violation of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) terms of service.

By making it a requirement for domain owners to provide their email address and other personal details and making them publicly accessible, the ICANN has somehow given them the accountability to use their websites ethically and legally. While this policy has neither eradicated nor even prevented cybercrime completely, it does provide a valuable resource for forensic investigation and threat prevention.

As such, these publicly available records have been used to trace sources of malware, detect and investigate fraud, as well as tracking down cyber attackers.

A registrant’s email address, for instance, allows investigators to directly contact the owner of a domain without having to go through other channels. Email addresses are also a handy resource for domain disputes and complaints about copyright infringement, among other things. WHOIS data, in its totality, is an abundant reservoir that aids organizations in strengthening their cybersecurity posture.

The Premise

In this comprehensive study, however, we found a significant number of redacted domain registrant email addresses. One justification for this could be the ICANN’s adherence to laws such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). But how does privacy protection affect cybersecurity processes that range from threat detection and prevention to incident response and investigation?

The odds are that cybercriminals are taking advantage of the anonymity the option provides and are increasingly using anonymously registered domains maliciously to attack organizations. With this premise in mind, this paper examines the evolution of WHOIS data availability, the volume of records with redacted email addresses, and the implications of information redaction.

Sources of Data

This study covers 1,334 top-level domains (TLDs) and 285,238,124 domains within these TLDs. We examined five of the original or old generic TLDs (gTLDs), namely:

- .com

- .org

- .net

- .biz

- .info

We also looked at email redaction among the top 25 new gTLDs:

- .top

- .club

- .loan

- .vip

- .shop

- .work

- .ltd

- .app

- .live

- .win

- .blog

- .life

- .cloud

- .online

- .stream

- .world

- .bid

- .link

- .wang

- .site

- .today

- .rocks

- .trade

- .xyz

- .review

For the country-code TLDs (ccTLDs), the paper examined the following:

- .fr

- .au

- .it

- .ca

- .us

- .in

- .asia

- .hk

- .sg

- .nyc

Aside from email redaction in these TLDs, we also took into consideration the monthly Domain Abuse Activity Reporting of the ICANN to obtain information on the number of domains that are possibly abused.

WHOIS After GDPR: Who Can See Who?

WHOIS is a search and response protocol that allows anyone to look up the details of a domain’s owner. It answers the question, “Who is responsible for this domain?” – hence the name. This information is called WHOIS data and may include the name, email address, phone number and address of the registrant as well as the domain’s administrative, technical, and billing contacts.

WHOIS data is stored in different databases maintained by various registrars and registries, all of whom need ICANN accreditation to operate.

Registrars have been required to publish their registrants’ WHOIS data since the 1980s, but that changed in May 2018, when the ICANN introduced the Temporary Specification for gTLD Registration Data as a way for registry operators to comply with the GDPR without forsaking its policies. The critical points of this new policy are outlined below.

- Registrars are still required to collect registration data from domain owners, but divulging personal data is only allowed to users with legitimate reasons.

- Legitimate and proportionate purposes include those related to “law enforcement, competition, consumer protection, trust, security, stability, resiliency, malicious abuse, sovereignty, and rights protection.”

- Since the contact information of registrants is no longer publicly available, registrars are required to put up a generic email address or an online contact form, so interested people still have a way to get in touch with the registrant.

While all these restrictions are under a temporary guideline, the ICANN’s proposal for permanent GDPR compliance suggests that access to full WHOIS data is set by using a tiered or layered framework, depending on the legitimate purpose of queries.

Redaction of Contact Emails: The Data

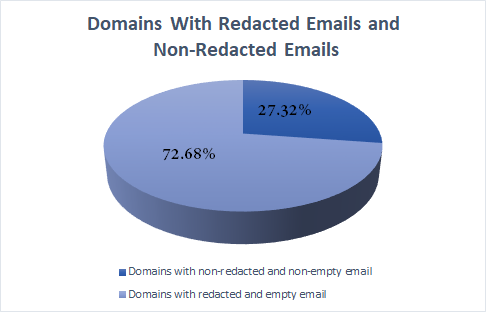

In line with this development, we checked 285,238,124 domains distributed across more than 1,333 gTLDs and found that only 77,918,723 domains (27.32%) have registrant email addresses. The rest — exactly 207,319,401 (72.68%) — did not include any email addresses.

WHOIS Registrant Email Address Redaction Comparison: Old gTLDs, New gTLDs, and ccTLDs

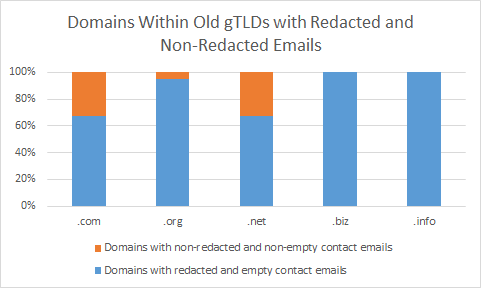

We found that 67.55% (more than 106 million) of .com domains, 95.10% (almost 19 million) of .org domains, and 67.49% (close to 16 million) .net domains do not have registrant email addresses. Almost all of the .biz and .info domains do not have registrant email addresses either.

The table below shows the exact number of domains with redacted and non-redacted email addresses for each old gTLD.

| Old gTLD | Total Domain Count | Domains with Redacted Email Addresses |

Domains with Nonredacted Email Addresses |

|---|---|---|---|

| .com | 157,261,416 | 106,236,954 | 51,024,462 |

| .org | 198,64,606 | 18,890,454 | 974,152 |

| .net | 23,601,444 | 15,929,125 | 7,672,319 |

| .biz | 3,664,389 | 3,659,863 | 4,526 |

| .info | 9,069,995 | 9,063,340 | 6,655 |

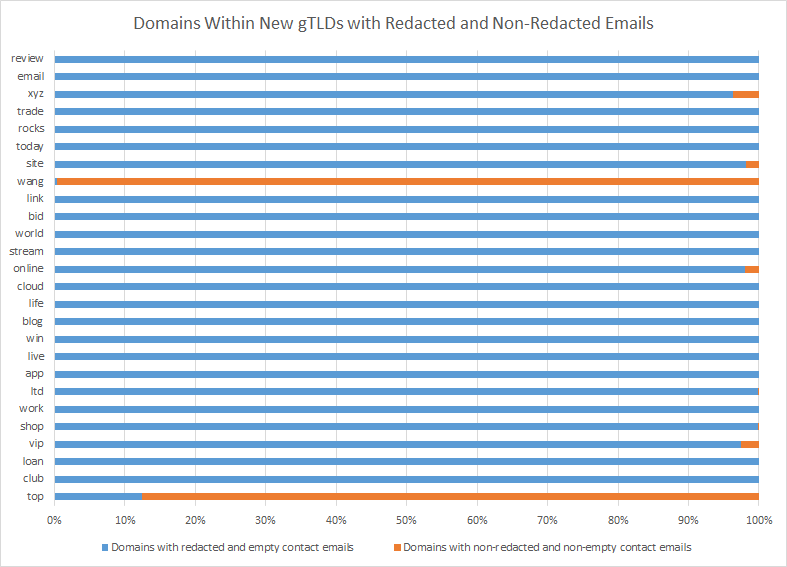

We also examined the 25 most popular new gTLDs and found that a majority (more than 99%) do not have registrant email addresses. .Wang and .top domains were the least redacted, on the other hand. Only 0.37% of .wang and 12.49% of .top domains do not have registrant email addresses.

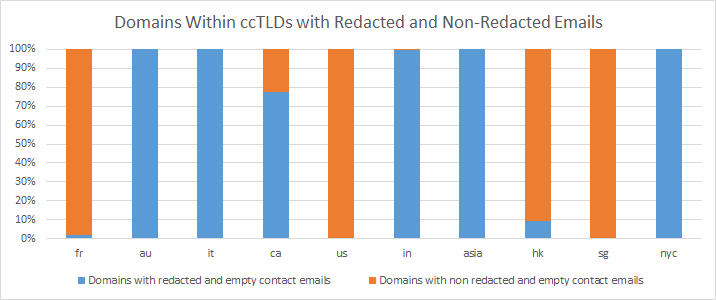

Looking at the ccTLDs, meanwhile, revealed that five of the most used ccTLDs have close to 100% email address redaction, particularly for .au, .it, .in, .asia, and .nyc domains. More than a third (77.66%) of .ca domains do not have registrant email addresses, while the rest — particularly .fr, .us, .hk, and .sg domains — indicate email contact details.

Redaction of Contact Emails: The Implications

With the majority of registrant email addresses and other personal information hidden from the public and accessible only to authenticated users, the starting point for cybersecurity incident response and investigation — WHOIS data — becomes unavailable.

Implication #1: Cybercriminals Are Gaining Confidence

Privacy protection for domain registrants somehow sent the wrong message to people with ill intentions: they are less accountable for domain ownership. The anonymity that private registration provides has given attackers confidence to obtain domains for their attacks without divulging their true identities and locations. Indeed, our research has revealed recently that there is a tremendous amount of typosquatted domains registered every day, and all of them have redacted WHOIS data.

In the guise of protecting their privacy, cybercriminals can more easily register domains for typosquatting or URL hijacking. For example, they may register misspelled variations or internationalized versions of popular domains to take advantage of people who are prone to making typos when accessing sites.

Several typosquatted domains can predominate in phishing campaigns. Because some misspellings are easy to miss, victims have often given out their credentials before realizing they are on the wrong page. The more popular a website is, the more likely it is to be spoofed. Banks, credit card providers, online invoicing companies, media outfits, and other reputable institutions make up the list of most-spoofed entities.

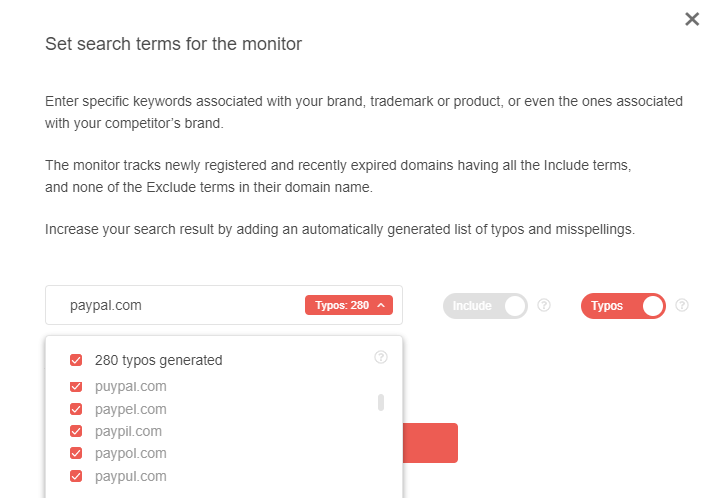

For instance, when we key in PayPal (the second most-spoofed site) using Brand Monitor, the tool alerts us instantly that 280 misspelled variants of the brand would be included in our tracker.

Adversaries can use any of these domains to launch phishing campaigns targeting PayPal users.

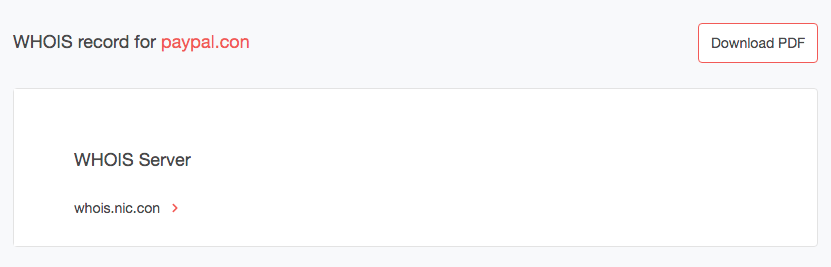

We ran a WHOIS search for one of the misspelled domains — paypal[.]con — and found that it is available for registration.

That means any enterprising cybercriminal can easily create a fake PayPal page on this domain and use it for phishing attacks. He/she is likely to get less careful typists to visit it too, given that “n” and “m” lie next to each other on the keyboard.

Brand Monitor and WHOIS Search are part of our Domain Research Suite, which site owners can use to detect, investigate, and defend against threats such as typosquatting, website spoofing, and phishing.

Implication #2: When It Comes To gTLDs, Old Does NOT Mean Reputable

The misspelled domain paypol[.]com (notice the typo “o” instead of the second “a”) uses a legacy gTLD, but that does not mean it is legitimate or trustworthy. This fact leads us to a critical point in our data analysis: A domain’s TLD is no longer a reliable indicator of its reputability.

In the past, when people ask how they can determine if a website is reliable, they were often advised to look at its gTLD. Our data, however, shows that the majority of the domains sporting the oldest gTLDs do not have any email addresses. And so if these end up used in attacks, conducting a forensic investigation would be more challenging. Of course, the mere fact that the registrant's data are redacted does not mean itself that a domain is malicious.

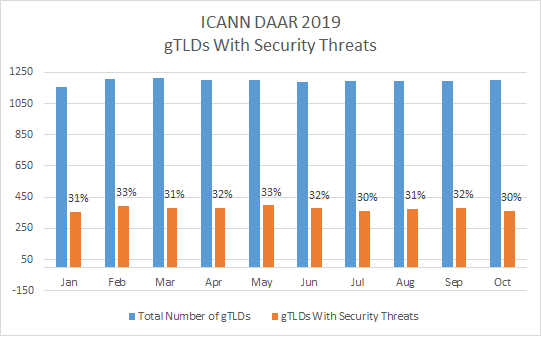

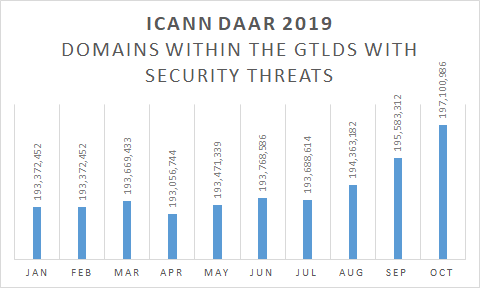

We also examined the ICANN’s latest Domain Abuse Activity Reporting (DAAR) report and found that more than 30% of all gTLDs had at least one security threat from January to October 2019.

That translates to more than 193 million domains possibly being used each month maliciously. The peak so far this year was seen in October. A total of 197,100,986 domains within 364 gTLDs had ties to security threats.

So where do these security threats come from? We’ve recently conducted a research on the role new gTLDs in cybercrime showing that while the number of malicious domains remains relatively constant in legacy gTLDs, a clear upward trend in their absolute is observable in the new ones.

However, while we see a constant rise in the number of new gTLDs used in cyber attacks, the old ones are not exempted either. There is no longer a clear dividing line between new and old gTLDs when it comes to reputability and reliability, as cybercriminals bombard the Internet with thousands of new domains each day.

Implication #3: Security Teams Need to Beef Up Their Cybersecurity Posture with Data Feeds

As more and more domains are used maliciously, the attack surface also grows. As such, security teams and forensic investigators need to employ more sophisticated methods to combat cybercrime and attacks.

The key to strengthening any organization’s security posture is real-time incident detection and response. Whether an organization employs a threat intelligence platform (TIP), a security information and event management (SIEM) tool, or a security orchestration, automation, and response (SOAR) solution, these all require one thing — quality data to analyze and act on.

Even if personal data is redacted from WHOIS records, domain research and monitoring tools such as the Domain Research Suite can still return useful results that can serve as security teams’ starting points for in-depth investigations.

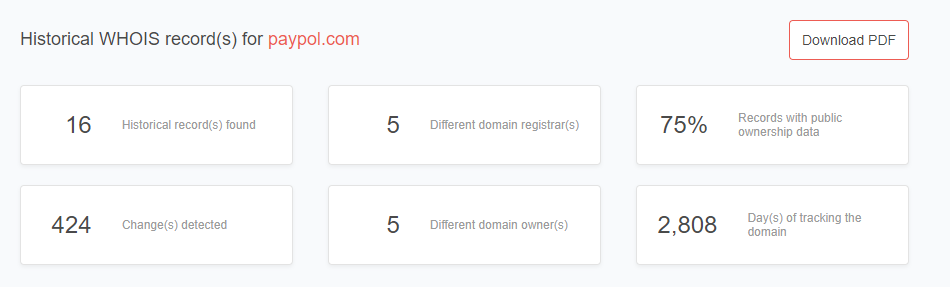

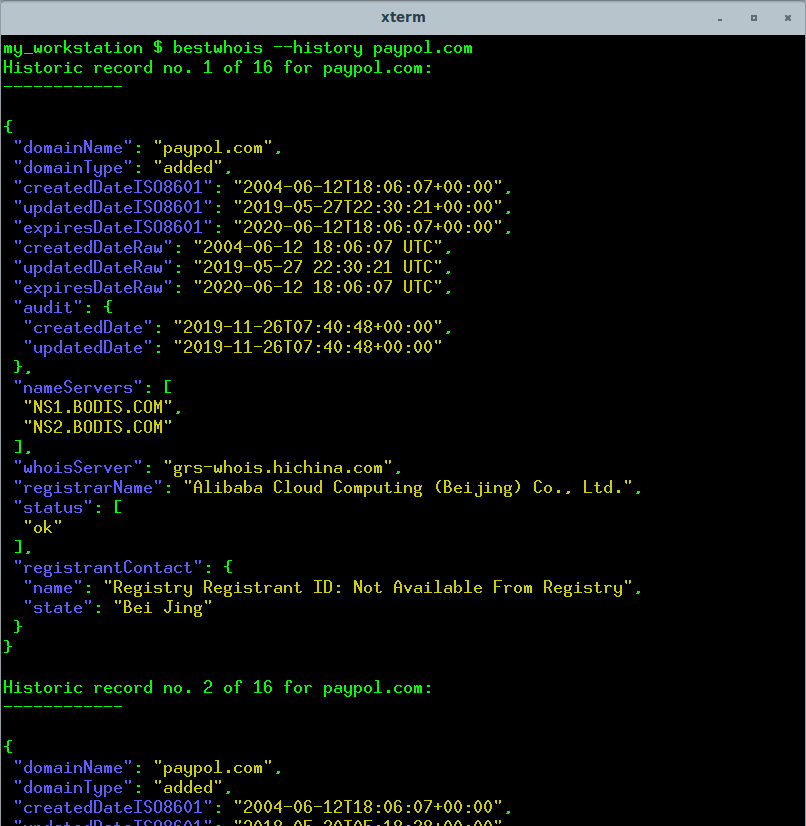

One such tool is WHOIS History Search, which returns a domain’s entire ownership history, including WHOIS data, before redaction. We chose the misspelled variant of paypal.com—paypol[.]com — because its current WHOIS record does not have a registrant email address.

Among the data that WHOIS History Search provides are the domain’s historical records arranged by date (from newest to oldest):

- 14 November 2019

- 24 September 2018

- 12 July 2018

- 13 January 2018

- 26 September 2017

- 10 August 2017

- 28 December 2016

- 23 April 2016

- 08 April 2015

- 30 September 2014

- 28 March 2014

- 24 November 2013

- 24 July 2013

- 10 April 2013

- 17 September 2012

- 06 March 2012

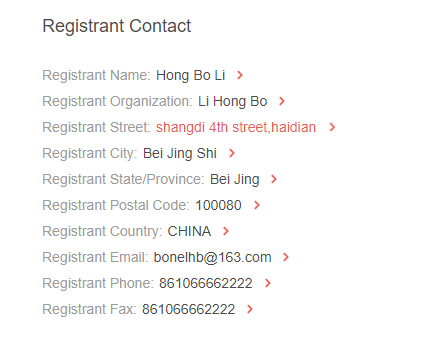

We looked at each record and found that the email address for the first three has been redacted. But the records from 13 January 2018 onward can give investigators and incident response teams a starting point for their inquiries.

As it turns out, the domain’s registrant remained the same from when the domain was created on 17 September 2012 up until 13 January 2018. The registrant details were only redacted when it changed hands.

Note that a similar result for paypol[.]com could also have been found by using our command-line WHOIS tool:

Conclusion

Privacy protection is a global concern as cybercrime, such as identity theft, continues to rise to alarming levels. But when it comes to WHOIS data, the ICANN’s dilemma of balancing between protecting registrants’ privacy and making them accountable for their properties is evident. The latter requires making WHOIS data publicly available even if for registrars and the ICANN it means paying hefty fines.

If the ICANN redacts registrants’ personal details to protect their privacy and comply with policies like the GDPR, the result could be somewhat unintended. Cybercriminals would gain more confidence because they would be harder to trace. Crimes using malicious domains could rise, and incident response teams and forensic investigators would find it even more difficult to solve cases.

Although the ICANN’s current stance leans more toward making domain owners accountable for their actions, it has temporarily instructed registrars to redact registrants’ personal data from WHOIS records.

In light of this, security teams and forensic investigators need to find ways to glean more insights from WHOIS records. They can use tools such as Brand Monitor and Domain Monitor, for instance, to get real-time alerts related to their brands, thus enabling them to protect against potential abusers. They can also rely on WHOIS History Search to get more insights into any domain despite current restrictions.

Read other articles