Hot on the Trail of Compulsive Brand Squatters — The Complete Research

By Alexandre François, Head of Marketing & Security Researcher at WhoisXML API.

Note: Check our webcast “Hot on the Trail of Compulsive Brand Squatters” for an overview of the results discussed in this report as well as related discussions by our security researchers.

Domain brand squatters refer to individuals or entities who register domain names resembling those of legitimate companies. These domains are commonly known as “look-alike domains” or “typosquatting domains.”

Brand squatters may have several tricks up their sleeves, including the sale of counterfeit products and the execution of phishing and malware campaigns. In this research, we are primarily interested in brand squatting activities that could lead or may have already led to phishing campaigns.

We collected more than 13,000 typosquatting domains registered within two days and categorized them into roughly 2,400 groups. These domains satisfy two requirements that hint at bulk registration—they closely resemble one another and were registered on the same day. Then for a period of 14 days from the day after their registered date, we checked daily if the domains were detected by major malware engines.

Below are our key findings:

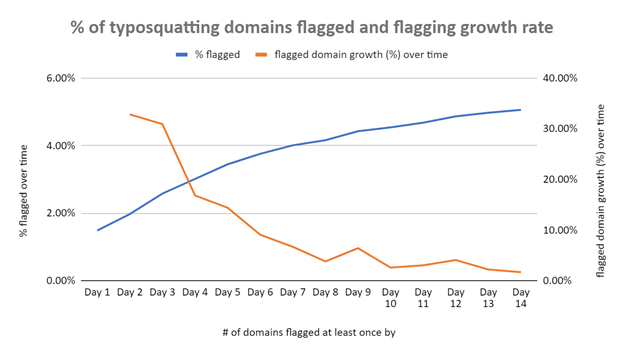

- 3.4 times more domains were flagged by day 13 compared to day 1. More specifically, 665 domains (5% of our sample) were reported as “dangerous” by day 13 compared to 195 domains (1.48%) on day 1.

- 89 out of the 2,432 (3.66%) typosquatting domain groups identified had at least one member reported as malicious by day 1. This number went up to 176 groups (7.24%) by day 13.

- Considering bulk registration and grouping dynamics as an early-warning mechanism allowed us to identify 700 suspicious domains related to typosquatting groups that may have been missed by traditional malware engines.

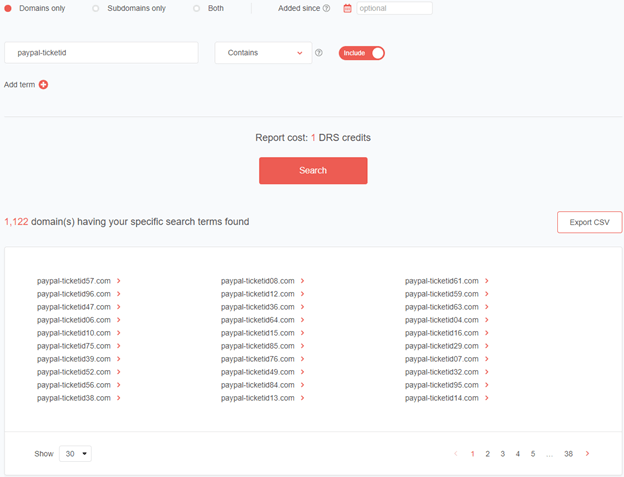

- A discovery analysis starting from a group of eight PayPal-related typosquatting domains enabled us to identify a total of 1,122 domains, accounting for 140 times the size of the initial group with the same or similar characteristics studied.

- A subsequent discovery and enrichment analysis led us to identify more financial service companies that could be impersonated by the same brand squatter across dozens of domains.

Methodology and Data Set

Using files from the Typosquatting Data Feed for 11–12 July 2021, we ran an experiment to identify how many of the sample typosquatting domains were dubbed “dangerous” over time using Domain Malware Check API.

The initial sample consisted of 7,285 domains for 11 July and 5,867 domains for 12 July. They were classified into groups of different sizes, as per the mechanics of the Typosquatting Data Feed (i.e., identifying groups of similar-looking domains registered on the same day).

Then for 14 days from the time they appeared in the Typosquatting Data Feed, we ran the domains via Domain Malware Check API daily and documented the results in this paper. The rationale for this was that an increasing number of domains would logically be found “dangerous” at least once over time.

For access to the complete domain list analyzed in this post and the enrichment done, you can contact us at [email protected] or fill out this form.

Analysis

As previously mentioned, this paper focuses on the notion that certain groups of typosquatting domains were probably used in malicious campaigns, hence the use of Domain Malware Check API. We did a three-part analysis of the data set:

- Analysis of the number of malicious typosquatting domains and groups

- Analysis of a targeted typosquatting group comprising eight PayPal-related domains

- Footprint expansion of the targeted PayPal-related typosquatting group

Malicious Typosquatting Domains

We listed the number of domains flagged “dangerous” at least once within the two-week period in the following tables:

| 11 July 2021 Typosquatting File | Cumulative Number of Malicious Domains | Total Number of Domains | Malicious Domains (%) | Malicious Domain Growth Rate (%) |

| Day 1 | 113 | 7,286 | 1.55% | |

| Day 2 | 144 | 7,286 | 1.98% | 27.43% |

| Day 3 | 186 | 7,286 | 2.55% | 29.17% |

| Day 4 | 222 | 7,286 | 3.05% | 19.35% |

| Day 5 | 247 | 7,286 | 3.39% | 11.26% |

| Day 6 | 274 | 7,286 | 3.76% | 10.93% |

| Day 7 | 295 | 7,286 | 4.05% | 7.66% |

| Day 8 | 309 | 7,286 | 4.24% | 4.75% |

| Day 9 | 333 | 7,286 | 4.57% | 7.77% |

| Day 10 | 343 | 7,286 | 4.71% | 3.00% |

| Day 11 | 351 | 7,286 | 4.82% | 2.33% |

| Day 12 | 372 | 7,286 | 5.11% | 5.98% |

| Day 13 | 383 | 7,286 | 5.26% | 2.96% |

| Day 14 | 391 | 7,286 | 5.37% | 2.09% |

Table 1: Number of typosquatting domains identified on 11 July 2021 that were flagged “dangerous” at least once over time and other relevant statistics

| 12 July 2021 Typosquatting File | Cumulative Number of Malicious Domains | Total Number of Domains | Malicious Domains (%) | Malicious Domain Growth Rate (%) |

| Day 1 | 82 | 5,868 | 1.40% | |

| Day 2 | 115 | 5,868 | 1.96% | 40.24% |

| Day 3 | 153 | 5,868 | 2.61% | 33.04% |

| Day 4 | 174 | 5,868 | 2.97% | 13.73% |

| Day 5 | 206 | 5,868 | 3.51% | 18.39% |

| Day 6 | 220 | 5,868 | 3.75% | 6.80% |

| Day 7 | 232 | 5,868 | 3.95% | 5.45% |

| Day 8 | 238 | 5,868 | 4.06% | 2.59% |

| Day 9 | 249 | 5,868 | 4.24% | 4.62% |

| Day 10 | 254 | 5,868 | 4.33% | 2.01% |

| Day 11 | 264 | 5,868 | 4.50% | 3.94% |

| Day 12 | 268 | 5,868 | 4.57% | 1.52% |

| Day 13 | 271 | 5,868 | 4.62% | 1.12% |

| Day 14 | 274 | 5,868 | 4.67% | 1.11% |

Table 2: Number of typosquatting domains identified on 12 July 2021 that were flagged “dangerous” at least once over time and other relevant statistics

The tables above show that the number of domains flagged “dangerous” on day 14 is about 3 times higher than that recorded on day 1. More precisely, if the number of domains from both files are combined, 195 domains were flagged “dangerous” on day 1 compared with 665 on day 14, which translates to 3.4 times more.

The aggregated information from Tables 1 and 2 are summed up below.

| 11–12 July 2021 Typosquatting File | Cumulative Number of Malicious Domains | Total Number of Domains | Malicious Domains (%) | Malicious Domain Growth Rate (%) |

| Day 1 | 195 | 13,154 | 1.48% | |

| Day 2 | 259 | 13,154 | 1.97% | 32.82% |

| Day 3 | 339 | 13,154 | 2.58% | 30.89% |

| Day 4 | 396 | 13,154 | 3.01% | 16.81% |

| Day 5 | 453 | 13,154 | 3.44% | 14.39% |

| Day 6 | 494 | 13,154 | 3.76% | 9.05% |

| Day 7 | 527 | 13,154 | 4.01% | 6.68% |

| Day 8 | 547 | 13,154 | 4.16% | 3.80% |

| Day 9 | 582 | 13,154 | 4.42% | 6.40% |

| Day 10 | 597 | 13,154 | 4.54% | 2.58% |

| Day 11 | 615 | 13,154 | 4.68% | 3.02% |

| Day 12 | 640 | 13,154 | 4.87% | 4.07% |

| Day 13 | 654 | 13,154 | 4.97% | 2.19% |

| Day 14 | 665 | 13,154 | 5.06% | 1.68% |

Table 3: Number of typosquatting domains identified on 11–12 July 2021 that were flagged “dangerous” at least once over time and other relevant statistics

It’s also interesting to note that the number of additional domains being flagged “dangerous” daily decreases over time. In fact, between day 1 and day 2, we saw a 27.43% increase for the 11 July data and a 40.24% hike for the 12 July data. However, between day 13 and day 14, that growth rate dropped to 2.09% (11 July) and 1.11% (12 July). The chart below reflects this trend, along with the number of domains flagged “dangerous” over time.

Figure 1: Number of typosquatting domains identified on 11–12 July 2021 that were flagged “dangerous” at least once over time.

Malicious Typosquatting Groups

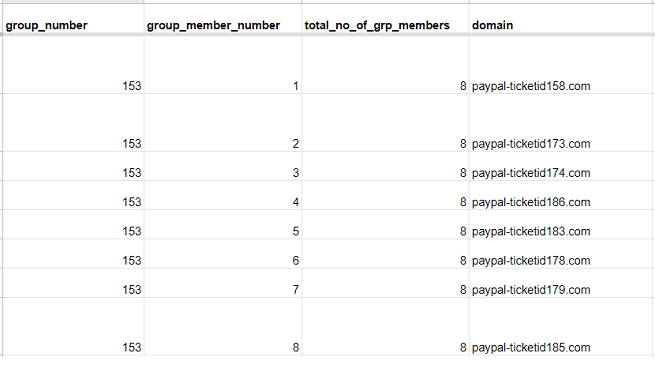

As noted earlier, the Typosquatting Data Feed detects groups of similar-looking domains that could be indicative of malicious behavior. Here is an example of a group found in the 11 July file:

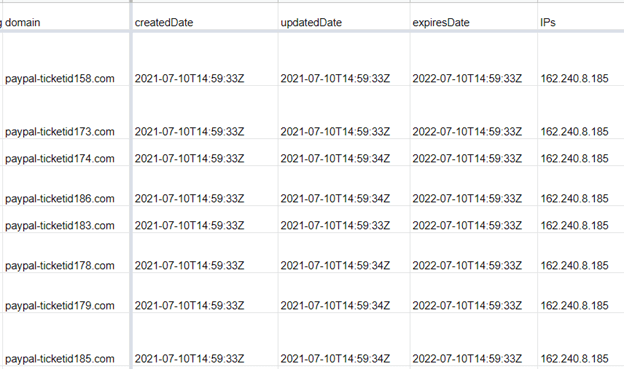

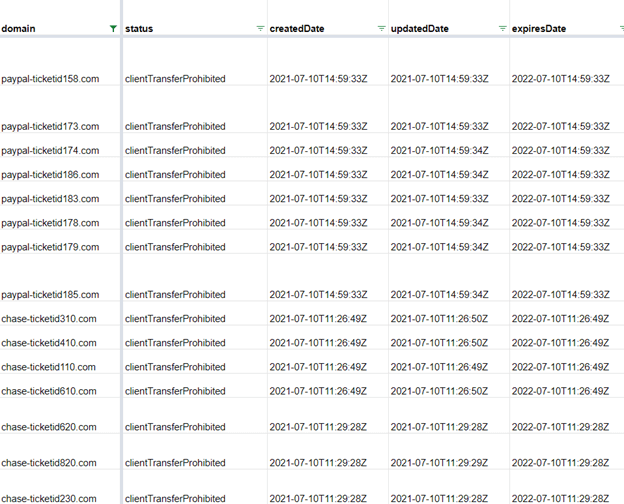

Figure 2: Typosquatting group identified on 11 July for the string “paypal-ticket”

As shown in greater detail later on, this group contains domains that malware engines have flagged “malicious.” For instance, paypal-ticketid158[.]com was still dubbed as such at the time of writing:

![Figure 3: Screenshot of Threat Intelligence Platform (TIP) report for paypal-ticketid158[.]com](https://main.whoisxmlapi.com/images/solutions/white-papers/hot-on-the-trail-of-compulsive-brand-squatters-the-complete-research/figure-3.png)

Figure 3: Screenshot of Threat Intelligence Platform (TIP) report for paypal-ticketid158[.]com

However, not every domain in this group was initially found dangerous, even if each contained the “paypal-ticketid” string.

A potential explanation for this is that threat actors may have decided to use the domains gradually. They could have found it convenient to register a pool of domains to execute campaigns faster. In other words, they may have used only a few domains at the onset of their attack. If the first set of domains gets blocked, they could switch to another set they already own and have ready for action.

This possible explanation raises the question of whether it would be wise to monitor or block entire groups of typosquatting domains upfront, even if only one or a few of their members are found “dangerous.” Assuming this premise is sound, we could look at other sets of statistics at the group level.

For 11–12 July, 1,296 and 1,136 groups of similar domains were identified, respectively. Table 4 and Figure 4 shows the number of groups with at least one member flagged “dangerous” over time for both dates.

| 11–12 July 2021 Typosquatting File | Cumulative Number of Malicious Groups | Total Number of Groups | Malicious Groups (%) | Malicious Group Growth Rate (%) |

| Day 1 | 89 | 2,432 | 3.66% | |

| Day 2 | 104 | 2,432 | 4.28% | 16.85% |

| Day 3 | 124 | 2,432 | 5.10% | 19.23% |

| Day 4 | 137 | 2,432 | 5.63% | 10.48% |

| Day 5 | 150 | 2,432 | 6.17% | 9.49% |

| Day 6 | 159 | 2,432 | 6.54% | 6.00% |

| Day 7 | 166 | 2,432 | 6.83% | 4.40% |

| Day 8 | 167 | 2,432 | 6.87% | 0.60% |

| Day 9 | 170 | 2,432 | 6.99% | 1.80% |

| Day 10 | 170 | 2,432 | 6.99% | 0.00% |

| Day 11 | 173 | 2,432 | 7.11% | 1.76% |

| Day 12 | 174 | 2,432 | 7.15% | 0.58% |

| Day 13 | 176 | 2,432 | 7.24% | 1.15% |

Table 4: Number of typosquatting groups identified on 11–12 July 2021 that were flagged “dangerous” at least once over time and other relevant statistics

Figure 4: Number of typosquatting domain groups identified on 11–12 July 2021 that were flagged “malicious” at least once over time

Should We Monitor Typosquatting Domains by Group?

When we compare the percentage of malicious domains against that of typosquatting groups with at least one domain flagged “dangerous,” we see a relatively wide gap, as reflected in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Percentage of typosquatting domains versus groups flagged “dangerous” at least once over time from the 11–12 July feed files

This gap exists notably due to the fact that typosquatting groups contain one or more suspicious members that may have been “missed” by traditional malware engines as per the example shown below.

Figure 6: Typosquatting group identified on 11 July for the string “paypal-ticket” with potentially “missed” domains highlighted

Now, considering the complete sample of 13,154 domains and 2,432 groups for the same analysis, we identified hundreds of suspicious and potentially “missed” domains over the course of two weeks. Table 5 shows the exact figures for the two days.

| 11–12 July 2021 Typosquatting File | Number of Suspicious Domains “Missed” |

| Day 1 | 689 |

| Day 2 | 703 |

| Day 3 | 794 |

| Day 4 | 805 |

| Day 5 | 813 |

| Day 6 | 825 |

| Day 7 | 817 |

| Day 8 | 807 |

| Day 9 | 790 |

| Day 10 | 780 |

| Day 11 | 781 |

| Day 12 | 763 |

| Day 13 | 755 |

Table 5: Number of domains that could be considered suspicious for belonging to a typosquatting group with at least one malicious domain

A Closer Look at Suspicious Typosquatting Groups

“Paypal-ticketid” Domains

We cited a typosquatting group earlier that contains the “paypal-ticketid” string. This group comprises eight domains, four of which were flagged “dangerous” every day for three days, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Typosquatting group containing the “paypal-ticketid” string with Domain Malware Check API results for three days

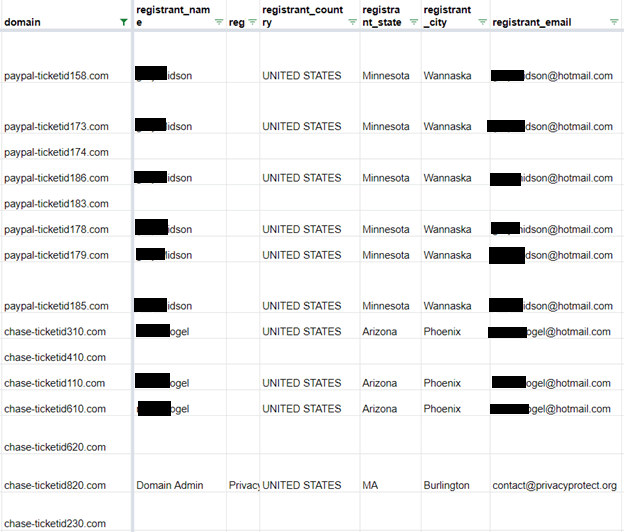

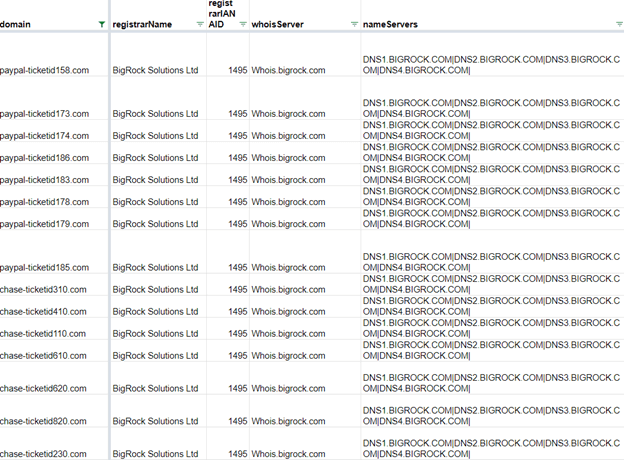

The latest WHOIS records of the domains appear to have the same registrant name and Hotmail email address (which we have kept hidden for privacy but uses the format “firstname.lastname[.]@hotmail[.]com”). The domains also have “BigRock Solutions” as the registrar name.

Figure 8: Registrant and registrar information of the “paypal-ticketid” domains

Aside from sharing the same registrant and registrar details, these domains also had matching creation, update, and expiration dates and IP addresses.

Figure 9: Relevant WHOIS record dates and IP resolutions of the “paypal-ticketid” domains

Even though we saw marked connections between the identified domain names, not all of them were dubbed “dangerous” from day 1 as shown in Table 6.

| Day | Number of Malicious Domains | Total Number of Domains in the Group | Malicious Domains (%) |

| Day 1 | 4 | 8 | 50.0% |

| Day 2 | 4 | 8 | 50.0% |

| Day 3 | 4 | 8 | 50.0% |

| Day 4 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 5 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 6 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 7 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 8 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 9 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 10 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 11 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 12 | 5 | 8 | 62.5% |

| Day 13 | 6 | 8 | 75.0% |

| Day 14 | 6 | 8 | 75.0% |

Table 6: Number of "paypal-ticketid" domains flagged “dangerous” over time

“Chase-ticketid” Domains

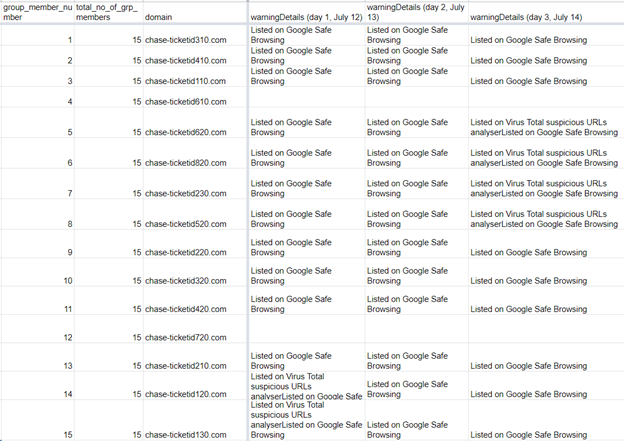

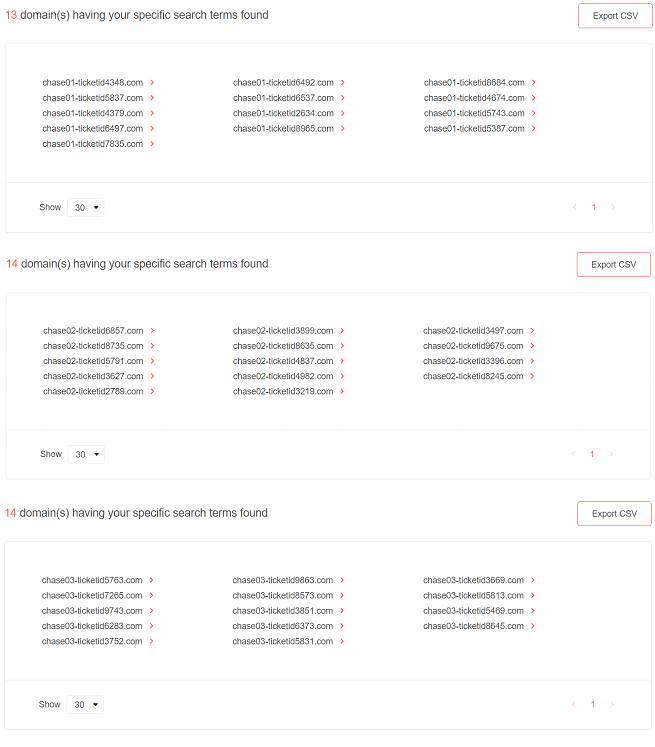

Looking at other domains found in the 11 July file, another group caught our attention because it somewhat looked similar to the “paypal-ticketid” domains. However, this second group repetitively used the string “chase-ticketid.”

Figure 10: Typosquatting group containing the “chase-ticketid” string with its Domain Malware Check API results

Note that this group has also been heavily flagged “malicious.” As of the first day of monitoring, 13 out of 15 domains were already marked as such.

Since the strings “paypal-ticketid” and “chase-ticketid” look similar (i.e., both had “tickedid” as a substring and used a popular brand name), it seemed interesting to check if a more profound connection exists between them. To check, we compared their WHOIS registration details.

First off, let’s look at their registrant details.

Figure 11: Registrant information of the “chase-ticketid” and “paypal-ticketid” domains

Besides the fact that the groups were from the same feed file (11 July), we also noticed that:

- The domains’ registrant country (where available) was the U.S.

- The two public email addresses followed the same pattern—firstname.lastname[.]@hotmail[.]com.

Second, looking at registrar and server information, we can see that this data is identical for the two groups.

Figure 12: Registrar information of the “chase-ticketid” and “paypal-ticketid” domains

Other data points, such as the status and creation, update, and expiration dates, are also the same for both groups.

Figure 13: Other WHOIS data points for the “chase-ticketid” and “paypal-ticketid” domains

Overall, there is a good chance that the same person or group could be behind the registration of the “chase-ticketid” and “paypal-ticketid” domains. Also, keep in mind that we are only looking at one day’s worth of typosquatting domain data. Who knows how many other branded “ticket-id” domains may have been registered over time? With that in mind, we proceeded to a more in-depth discovery analysis.

Footprint Expansion for the “paypal-ticketid” and “chase-ticketid” Groups

Domains & Subdomains Discovery, which is part of the Domain Research Suite (DRS), allowed us to identify domain footprints using advanced filtering criteria. It’s a good starting point for studying strings like “ticked-id.”

For instance, for the string “paypal-ticketid,” we found 1,122 domains. Compared to our eight initial domains in the 11 July typosquatting data feed, we discovered 140 times more potentially connected domains.

Figure 14: Domain discovery results for the “paypal-ticketid” string

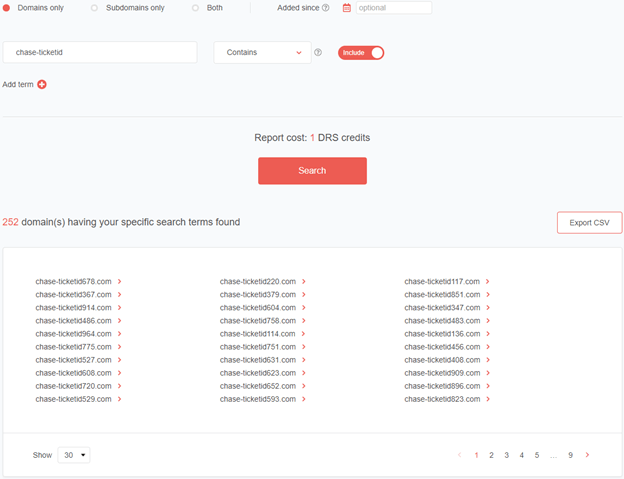

For the “chase-ticketid” string, we saw 16.8 times more domains (252 to be exact) from the initial group of 15.

Figure 15: Domain discovery results for the “chase-ticketid” string

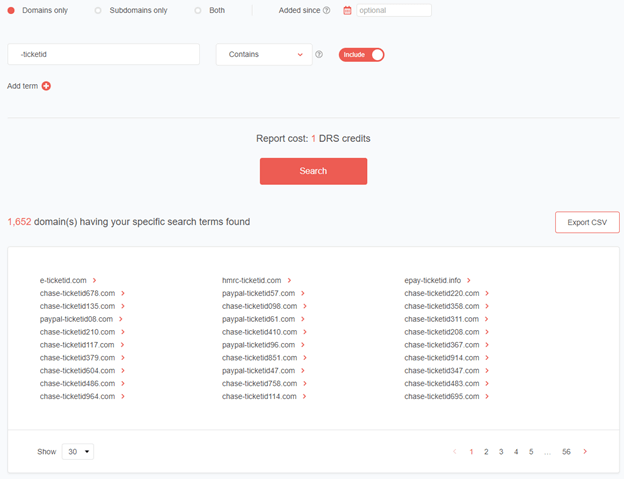

Broadening the analysis, it’s also possible to query only the “-ticketid” string to see if other brands appear. Doing so gave us a total of 1,652 domains or an additional 278 domains.

Figure 16: Domain discovery results for the “-ticketid” string

While using this shorter string is more prone to the inclusion of more false positives, going through the long list helped us identify other domains with different string variations, such as “chase01-ticketid,” “chase02-ticketid,” and “chase03-ticketid.”

Figure 17: Domain discovery results for the “chase-ticketid” string

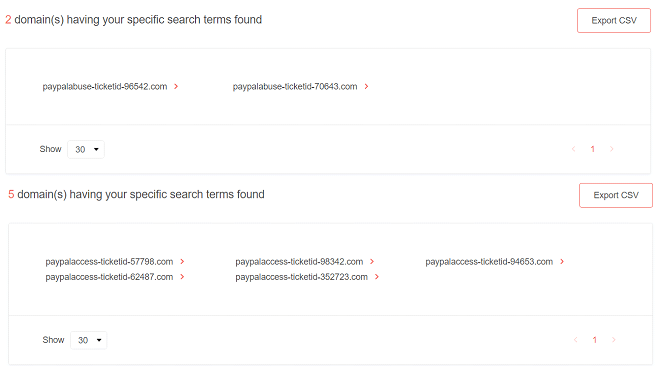

Examples of the additional results are “paypalabuse-ticketid” and “paypalaccess-ticketid” domains.

Figure 18: Domain discovery results for the “paypal-ticketid” string

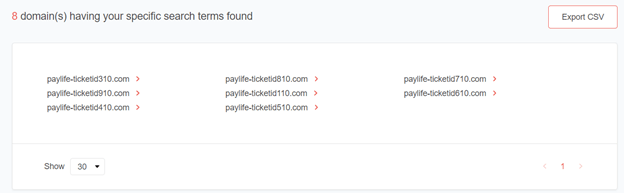

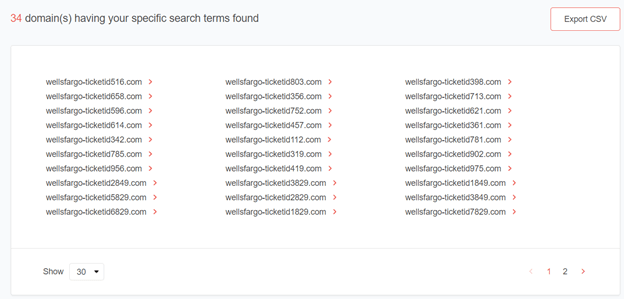

We also found other domains sporting other brands, including credit and debit card provider Paylife and financial service company Wells Fargo.

Figure 19: Domains containing the “paylife-ticketid” string

Figure 20: Domains containing the “wellsfargo-ticketid” string

WHOIS Analysis of “-ticketid” Domains

While we already identified a significantly larger campaign footprint, from 23 to 1,652 domains or 71 times the initial number of clues obtained from the Typosquatting Data Feed, it was interesting to determine if we could establish sufficient connections between the initial and expanded groups.

To do that, we did a bulk WHOIS lookup of the 1,652 domains. That gave us 307 domains with current WHOIS records. The significant discrepancy between 307 and 1,652 could be due to the speed at which the domains on our list are being taken down. Many of the “-ticketid” domains from the 11 July feed were flagged “dangerous” shortly after detection.

That said, for the 307 domains with current WHOIS records, we found that:

- 270 domains or 87.9% had the same registrar (BigRock Solutions Ltd.). This finding is similar to that found for the “paypal-ticketid” and “chase-ticketid” groups.

- 104 domains or 33.9% had Hotmail email addresses. Several of them had a similar email address structure (firstname[.]lastname@hotmail[.]com). Again, this was true for the “paypal-ticketid” and “chase-ticketid” groups.

Conclusion

While other typosquatting groups on the 11–12 July data feeds appear to be part of opportunistic domain parking activity, the PayPal and Chase typosquatting groups we cited are good illustrations of what brand squatting could look like. Brand squatting could come in droves, as shown by the hundreds of “-ticketid” domains we uncovered.

The actors behind brand squatting could be identified by analyzing WHOIS records, though there is a good chance the recorded public details we identified were aliases of some sort. Still, our analysis of the PayPal and Chase typosquatting domains and registration patterns hint at the same person or group behind their registration.

More significantly, the brand squatters identified in this research may have decided to progressively put their registered domains to work. In fact, some typosquatting domains were immediately flagged “malicious” by traditional malware engines while others in groups of bulk-registered domains may be missed for a few days until they become active.

With that in mind, it could be beneficial to consider typosquatting domain groups registered on the same day as early-warning indicators of phishing or malicious activity where one group member has been flagged as dangerous.

Read other articles